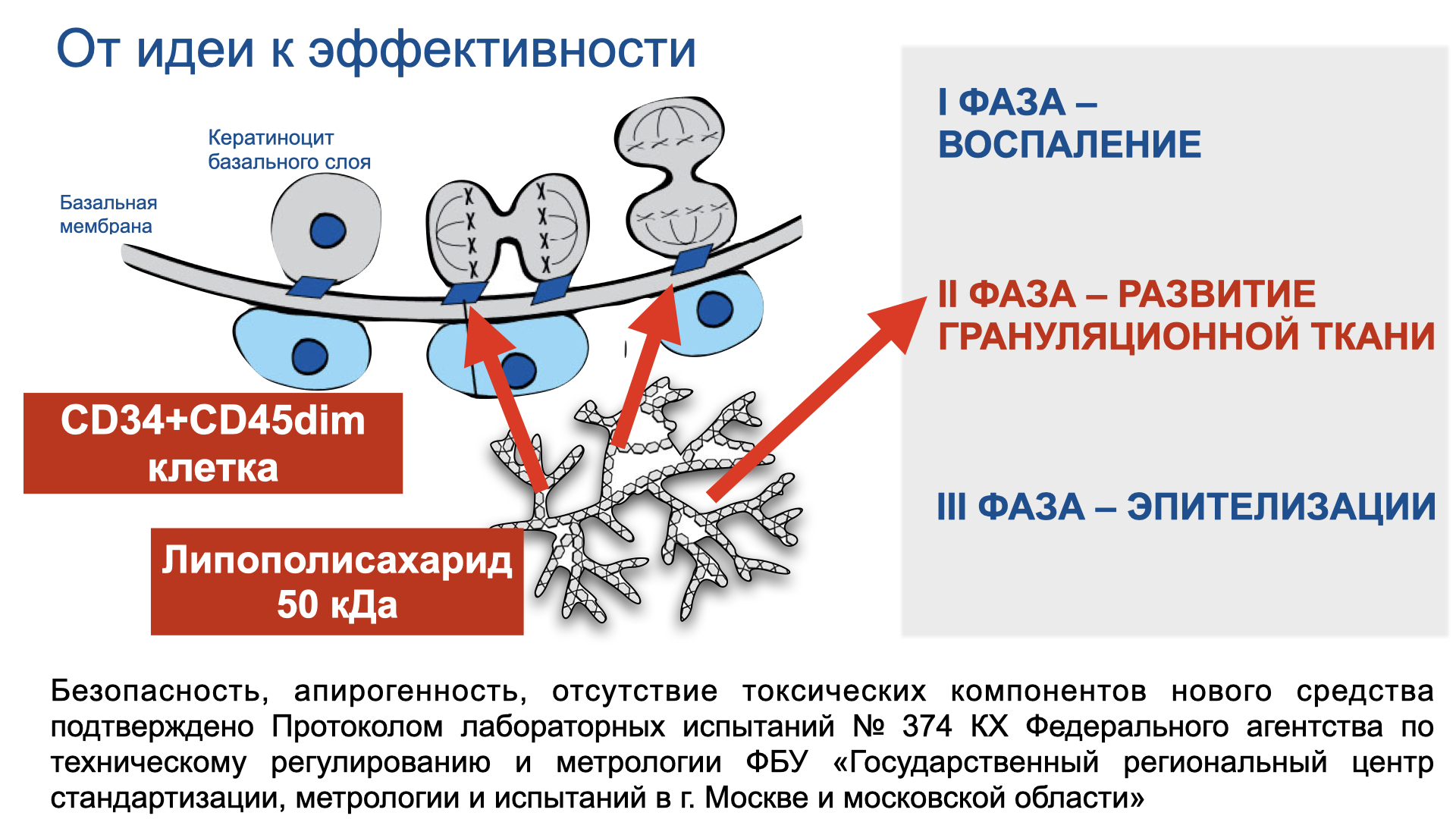

This mechanism is well studied. Starting from the early embryonic stages of skin development, cells divide symmetrically and parallel to the basal membrane, providing skin enlargement in the growing embryo, forming a unicellular layer. Subsequently, the cells on the basal membrane also divide symmetrically into themselves, which remain on the membrane, and asymmetrically into differentiating cells such that the mitotic spindle is directed perpendicular to the basal membrane.

The resulting daughter cells find themselves in unequal conditions, as one of them remains attached to the basal membrane and the other does not. This difference determines their further fate. Those that remain on the membrane are sensitive to adhesive molecules and maintain proliferation. Others, through the transient stage, enter the path of differentiation and, moving upwards, turn into keratinocytes, forming the multilayer epidermis.

On the other side of the basal membrane, among other things, so-called niche cells (CD34+) were found, which, when damage occurs, signal to the basal membrane cells how and at what rate they should divide. This happens through the above-mentioned signaling adhesive molecules of non-protein nature. This is a key area of our efforts if we want to control repair.